Tourism can be a support system for young men who spent years studying, collecting alms, and meditating.

ABOUT 10 YEARS AGO, IN the northern countryside of Laos, a boy named Sounanh Oulaxay was feeding buffalo when he noticed a few bald, barefoot men in orange robes walk by. When he asked his father about them, he was informed that they were Buddhist monks—and if he wanted to be a good man, he should think about becoming one. So he did: At the age of about 12, Sounanh moved to the city of Luang Prabang to become a novice.

In the spring, a hot haze—a result of the yearly crop-burning season—coats the low-lying buildings of Luang Prabang. Small temples were tucked into the corners of every street, orange robes hung from balconies, and monks used small brooms made of bundled sticks to sweep leaves away from golden statues of Buddha. Oulaxay spent several years studying and living in the temple, working his way toward becoming a monk. But his time in the monastery didn’t last.

On a steamy day in March 2019, Oulaxay meets with a group of American and Canadian tourists near the gate of an unassuming temple, Wat Paphaimisaiyaram, not far from the Mekong River. Now 19, he’s dressed in denim—the clothes of a layperson, not a monk. He discusses the rigid rituals and schedules of the novices: waking up at 3:30 a.m., chanting, collecting alms. Young novices go to school, he explains, while adult monks spend their days studying in the library, cleaning, or in a state of deep meditation. Monks are not allowed to interact with laywomen, he says, and should never try to shake their hands.

The visitors react with disbelief. They pepper him with questions. Oulaxay just smiles and answers: “People always say, ‘Oh my God, how do you do this?’ But here in Luang Prabang, this is all just normal.” An older man in a straw fedora asks politely, “Why did you leave the monastery?” Oulaxay, who was a novice for seven years in total, laughs. He mimics typing on a keyboard and makes a ‘ch ch ch’ sound. “I want to study computer science.”

IN LAOS, THERE IS A long tradition of young men leaving rural areas to to become novices in the city. Joining the holy life is a way of getting a decent education, two meals of sticky rice a day (Laos has the highest per capita consumption of sticky rice in the world), and shelter in a temple, which reduces the economic burden on families. Most importantly, joining the monastery brings families “merit.”

Merit is a key concept in Laotian Buddhism, according to Ian Baird, a geography professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison who has researched Buddhism in Laos. It has to do with karma, he explains: You do something good, then you gain a kind of spiritual credit for the future. “If a boy becomes a novice,” Baird explains, “his mother and father benefit, not materially, but otherwise.” As such, many families expect that at minimum, the eldest son in a family become a monk.

But what happens when you don’t want to be a novice anymore? Leaving a Laotian sangha, or Buddhist monastic order, is not in itself frowned upon. In fact, it’s commonplace. “In Laos, just having been in the sangha is taken as a very good thing for oneself and for the family,” says John Holt, a professor of Asian religious traditions at Bowdoin College. In other countries where Theravada Buddhism is widely practiced, such as Sri Lanka and Myanmar, former monks can sometimes face stigma. But in Laos, Holt says, “ordained monks who revert to the laity have an honorific word attached to their formal names. There is life-long prestige for having been a monk.”

Even so, the transition can be extremely difficult. In part because UNESCO considers Luang Prabang culturally significant, the rules for monks are strict compared to other cities in Laos, or in neighboring Buddhist countries such as Thailand. They are not allowed to ride on motorbikes, have cell phones, or attend university with local people. “Adjusting to lay life can be difficult, especially since there is no support system in play,” Holt says.

Many novices eventually leave monasteries in Luang Prabang for universities in cities like Vang Vieng or Vientiane, the Laotian capital. When Oulaxay left the monastery this year, he wanted to continue his studies. But he had no way to pay for university, and few practical skills besides meditation. As a way to cover the cost of living without his family in Luang Prabang, he continued learning English and became a tour guide.

OULAXAY ANSWERS MORE QUESTIONS AS the group of tourists enters the gates of Wat Paphaimisaiyaram. A few monks are quietly sweeping leaves near a giant gong. Oulaxay invites the visitors to remove their shoes and enter the temple, so that they can learn how to prostrate.

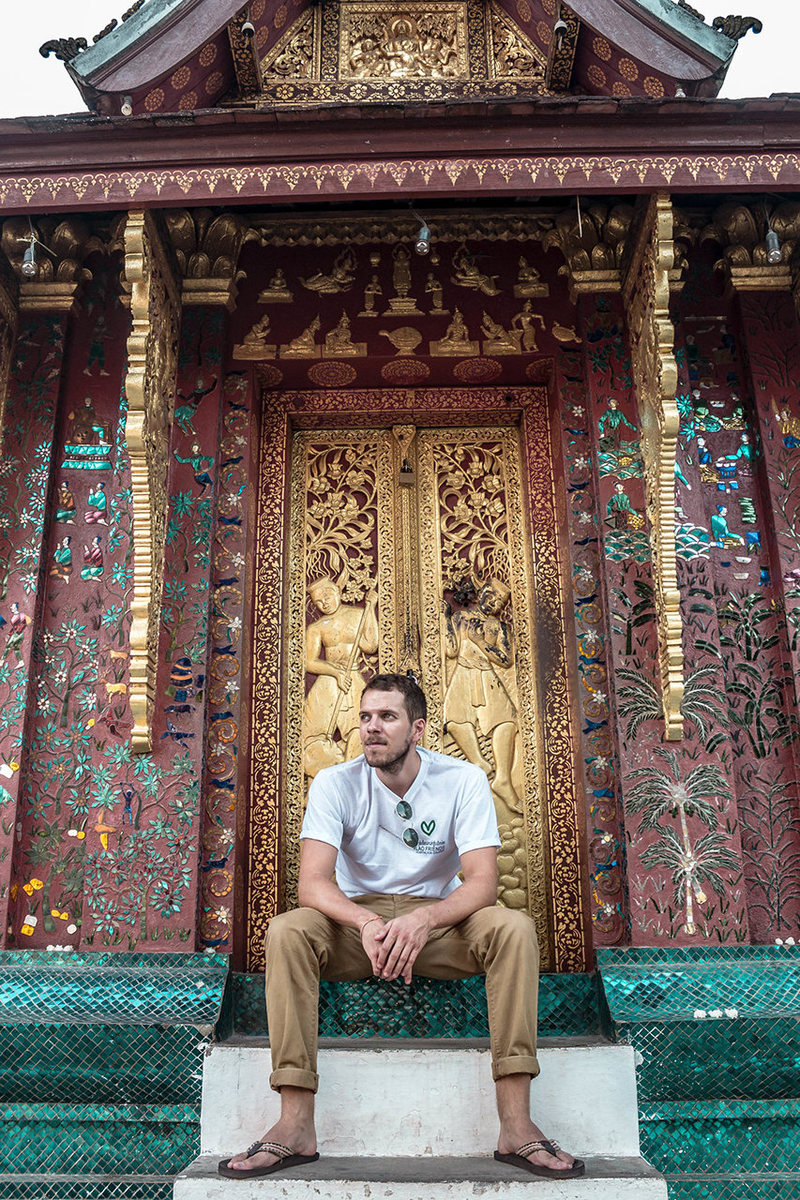

Oulaxay’s employer, “Orange Robe Tours,” is just a two-minute walk down the street from his tour. Luke Tavener, a 26-year-old from the United Kingdom, runs the business out of a small storefront on a dusty road. Tavener came to Laos in 2015 to teach English, and he began to notice a pattern in his classes: Ex-monks, some of them working as tuk-tuk drivers or waiters, wanted to gain a marketable skill. Tavener says he founded Orange Robe Tours so that former novices could find work as guides.

Luang Prabang’s tourism industry has blossomed in recent years because of its artistic energy, its proximity to the Mekong River, and its calm spirituality. There are signs all over the city asking tourists not to use flash photography in the early morning, when the monks collect alms, and to cover up if they enter a holy space. Ian Baird, the geography professor, suspects that many novices ultimately want to work in tourism.

Still, Orange Robe Tours portrays tourism as a good thing for those who have left a sangha. “Ex-monks and novices are able to find their way back into society, and laypeople learn what is appropriate in a temple—what clothing is appropriate, not to face their feet towards Buddha,” Tavener says*. “We have had a lot of trouble with tourists here. I have heard horror stories of people doing yoga in temples during chanting!”

On the day that a monk leaves the sangha, Tavener says, there is a small leaving ceremony. “You give your robes back and change into layperson clothes,” he says. “Then you are left to yourself.”

Sunti SouliPhone, another 19-year-old tour guide, moved to Luang Prabang to become a novice in 2010. This year, he decided to leave the temple and continue his studies. “When I decided to leave, a tear came down from my eye,” he says. “But for now, I don’t have much money, and I cannot live far from my mom.” SouliPhone adds that despite the difficulties, he works to live by the principles his abbot gave him before he left. “I want to learn about life outside, and how it’s different from inside. But I very much liked our lives inside, because it was very happy and quiet.”

SouliPhone is still unsure what he will do, now that he is no longer on his way to becoming a monk. He’s considering being a tour guide for good, or maybe an English teacher. But he still finds comfort in the Buddhist community. “We don’t know about the life outside yet,” he says. “Sometimes I feel a bit excited. I lived there for many years and my heart is in contact with the temple, so I go chanting every day. I promise myself I will not forget where I lived, and what I was before.”

Oulaxay is still friends with the people in his old temple, and he visits often. Once he has saved up enough money, he says, he hopes to attend university in Vientiane, where monks are more integrated into society. “I still wake up at 4 a.m. every day,” Sounanh says. Before the sun rises, he goes to pray in the temple where he once lived. “It is still very special to me.”

By Isobel Van Hagen